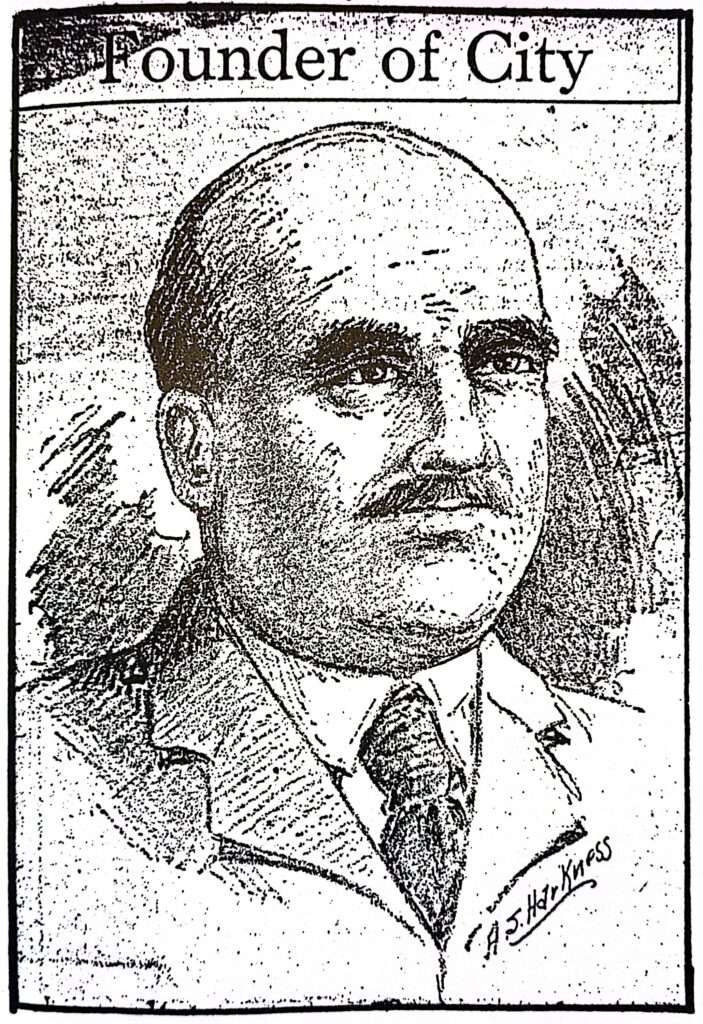

William Willmore is a name that many people living in Long Beach today may not recognize. Yet, this man played a crucial role in the founding of the city—a city that grew to become one of Southern California’s most vibrant coastal communities.

Willmore’s story is one of vision, ambition, hardship, and ultimately, tragic failure. Despite his efforts to create a thriving town along the Southern California coast, the city that he founded would prosper only after he had lost everything, including his dream.

The Visionary Dreamer

William Willmore arrived in Southern California in the early 1880s, a time when the region was still relatively undeveloped and sparsely populated. He saw in the coastline a potential for a new kind of community, one that would attract settlers looking for a better life in the sunny, temperate climate of Southern California.

Willmore’s vision was grand: a city with wide boulevards, parks, resort hotels, a bustling downtown district, and even a university campus. In pursuit of this dream, Willmore secured an option to purchase 4,000 acres of land from J. Bixby & Co. at a price of $25 per acre—an enormous sum at the time. He faced immediate challenges, not the least of which was the lack of easy access to the land.

The nearest train station, serviced by the Southern Pacific, was more than three miles away, making it difficult for potential buyers to visit the property. However, Willmore’s enthusiasm and optimism were unshakable, and he was determined to overcome these obstacles.

Building Willmore City

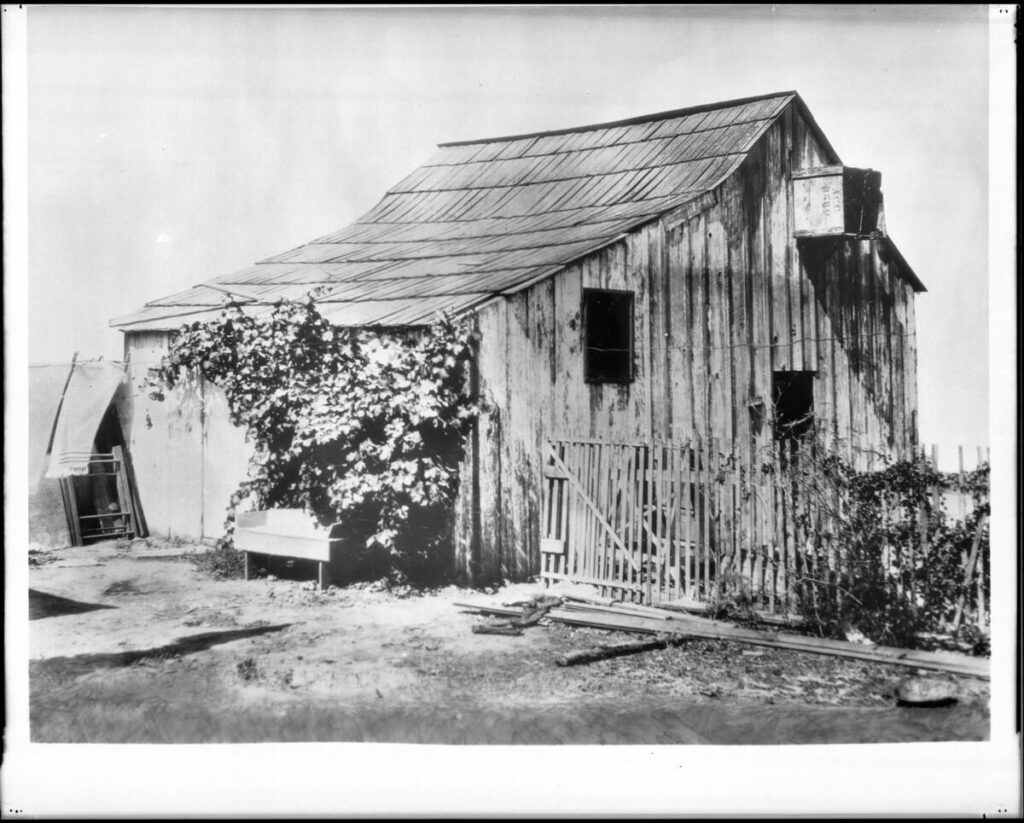

To solve the accessibility problem, Willmore along with Judge Robert Widney, founder of the University of Southern California, formed the American Colony Railway Co. and began constructing a rudimentary railroad to connect the land to the nearest train station in Wilmington. It was a daunting task—one that required laying three miles of track and building three bridges within just two months. The materials were scarce, and the tracks were made from pine strips, with redwood ties holding them together. Despite these challenges, the railroad was completed in time for an auction of lots in what Willmore now called Willmore City.

The day of the auction, however, did not go as planned. During the inaugural trip of the horse-drawn train, one of the pine strips gave way under the strain, tipping over a railway car full of passengers. Although the passengers managed to right the car and continue their journey, the event earned the railroad a nickname that would haunt it: the “Get Out and Push” railroad. Despite this setback, Willmore managed to sell thirty-six lots that day, with prices ranging from $125 for oceanfront property to $25 for lots further inland.

One notable aspect of these sales was a clause included in the property deeds—likely at the suggestion of Jotham Bixby’s wife, Margaret—that prohibited the sale of liquor on the properties. If any buyer violated this clause, the land would revert back to the original owners. The only exception to this rule was for hotels, which were essential to the development of the resort community that Willmore envisioned.

The Fall of Willmore City

Despite his best efforts, Willmore’s ambitious project quickly ran into financial trouble. The money from land sales trickled in slowly, while the expenses continued to mount. Funds were spent on necessary infrastructure such as water lines, as well as amenities like bathhouses and advertising. The payments to J. Bixby & Co., which were due in installments, became increasingly difficult to meet. The first two payments were missed, and Willmore’s financial situation became dire. By May 1884, Willmore’s resources had run out. Unable to pay the next installment, he was forced to surrender his contract to the Bixby Company for a mere $1. Defeated and heartbroken, Willmore left the town he had worked so hard to create.

The Transformation to Long Beach

Shortly after Willmore’s departure, a real estate firm named Pomeroy and Mills purchased the option on the land, along with additional acreage, for $240,000. They also paid Willmore $8,000 for the water system he had installed, a small consolation for the man who had lost his dream. One of their first acts was to rename the town, as “Willmore City” no longer seemed fitting with its founder gone. After some discussion, the name “Long Beach” was chosen, thanks to a suggestion by Belle Lowe, wife of the city’s first postmaster.

Under new management, the town began to flourish. The new directors, many of whom Willmore had previously dealt with, were men of considerable means. They pushed forward with the development plans that Willmore had envisioned, and with the influx of settlers driven by the Great Southern California Real Estate Boom of 1887, the town began to grow rapidly.

The Great Southern California Real Estate Boom

The real estate boom that hit Southern California in 1887 was driven by several factors: cheap train fares due to a price war between the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific railroads, a multitude of job opportunities at good wages, the appeal of the Southern California climate, and the speculative frenzy that the boom itself created. At one point, the price of a train ticket from the Missouri Valley to Southern California dropped to just $1, prompting tens of thousands of people to move west.

Land prices skyrocketed as a result. Land that had sold for $100 an acre in 1886 was being traded for $1,500 an acre by 1887. City lots that had been valued at $500 soared to $5,000 within a year. Had Willmore been able to hold on just a little longer, he might have reaped the rewards of the boom and seen his vision for the community realized.

Willmore’s Tragic End

Unfortunately, Willmore was not around to witness the success of the town he had founded. After leaving Willmore City, he returned to Southern California, where his later years were marked by poverty and despair. He ended up at the county poor farm in Downey, and in 1899, knowing that he was near death, he left the farm and returned to Long Beach—no longer Willmore City, but the town that had grown from his original vision.

He was discovered in the First Baptist Church by Ida Crowe, a kind woman who took him into her home. Other friends helped him set up a small fruit stand on Pine Avenue, but that business quickly failed as well. Willmore, embittered and defeated, spent his final days wandering the streets of the town he had founded, telling anyone who would listen about how he had been wronged.

William Willmore died penniless on January 16, 1901, in the Crowe home. He was buried in an unmarked grave at the Long Beach Municipal Cemetery. It wasn’t until 1913, twelve years later, that a marker was finally placed on his grave by the Signal Hill Civic League.

The Legacy of William Willmore

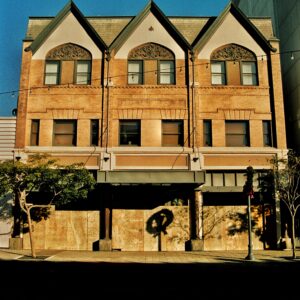

William Willmore’s story is a cautionary tale about the challenges of real estate development and the sometimes cruel twists of fate that can determine success or failure. His dream of creating a thriving community on the Southern California coast was ultimately realized, but only after he had lost everything. Today, Long Beach is a bustling city, home to hundreds of thousands of people, with a rich history and a vibrant cultural scene. Yet, the city’s origins as Willmore City, and the man who founded it, are largely forgotten. While the name “Willmore” still appears in certain areas of Long Beach—such as Willmore Avenue and the Willmore District—his story remains a largely untold part of the city’s history.

William Willmore may have died penniless and broken, but his vision for what would become Long Beach lives on in the city that grew from his dreams. He may not have lived to see it, but his legacy endures in the thriving community that stands as a testament to his ambition, determination, and foresight.